Reimagining libraries as conveners of information and innovation

Figure 1: Mapping the Geography of American Television News Knight News Challenge: Libraries closes today, Tuesday, Sept. 30, 2014. The challenge offers applicants a chance to share in $2.5 million by focusing on the question “How might we leverage libraries as a platform to build more knowledgeable communities?” Below, Kalev H. Leetaru, a data scientist and the Yahoo Fellow at Georgetown University, writes about libraries as centers of information innovation.

RELATED LINKS

“Libraries as leaders: An opportunity for our communities” by Chris Jowaisas on Knight blog (09/29/14)

“To build better libraries, start with the needs of people” by Emi Kolawole on Knight Blog (09/25/14)

“Powerful ideas push the boundaries of what libraries can be” by Stephanie Pereira (09/24/14)

“Make the most of your submission for Knight News Challenge: Libraries” by Chris Barr and John Bracken (09/23/14)

“Lesa Mitchell, Network for Scale: A new opportunity for libraries” on Knight blog (9/19/14)

“Lessons in sharing, from the public library” by Nate Hill on Knight blog (9/18/14)

“Bianca St. Louis, CODE2040: ‘I envision libraries as a creative space and entrepreneurial hub’” on Knight blog (9/18/14)

“Why Libraries?” by Sheila Murphy on Knight blog (9/17/14)

“Libraries cultivate connections, community and more in the digital age” by Anthony Marx on Knight blog (9/15/14)

“Can research libraries adapt to live up to their potential?” by Bernard Reilly on Knight blog (9/12/14) “Finding the sweet spot for libraries in the digital age” by Jill Bourne on Knight Blog (9/11/14)

“Knight News Challenge: Libraries opens for entries” by John Bracken on Knight Blog (9/10/14)

“Why Libraries [Still] Matter” by Jonathan Zittrain on Medium (9/10/14)

“News Challenge to explore role of libraries in the digital age” by John Bracken on Knight Blog (8/25/14)

“Knight News Challenge on Libraries offers $2.5 million for innovative ideas ” – Press Release (8/10/14)

Imagine a world in which libraries and archives had never existed. No institutions had ever systematically collected or preserved our cultural past: Every book, letter and document was created, read and immediately thrown away. Alternatively, what if everything had been kept and the Library of Alexandria had survived to present day, archiving all societal knowledge through the millennia? How would life be different in these two worlds, one of no history and one of all our history, and what can this suggest to us of the future role of libraries in society?

Today both of these worlds have become reality: Libraries ship the physical book world of our history off to storage, eliminating the serendipitous discovery of browsing, while the Web simultaneously creates a virtual Library of Alexandria that unifies societal knowledge. No longer do libraries serve as gatekeepers to the world’s information: The Web has democratized access to information and with a single mouse click provides far more than any single library could ever offer. Have libraries truly been rendered obsolete in the digital world?

For thousands of years libraries have acted as both stewards of information and as social centers forging communities around the dissemination of that information. The Library of Alexandria’s great value came not from merely being a large warehouse, but rather from its staff that acted as a giant living catalog of its collections, guiding scholars through its holdings, and the community that formed around those collections. In contrast, today’s global library of the Web is accessed in solitude, through keyword searches, forcing complex information needs to be artificially reduced to a single word or phrase, with incomplete and incorrect information often more accessible than reputable sources.

What if we could bring scholars, citizens and journalists together, along with computers, digitization and “big data” to reimagine libraries as centers of information innovation that help us make sense of the oceans of data confronting society today? Over the past year I have been exploring this model in collaboration with the Internet Archive, examining how its 19 petabytes of data, spanning 400 billion Web pages, half a million hours of television, and 600 million pages of digitized texts could be used to reshape our understanding of human society. The archive is unique in that its holdings span the historical past of digitized physical books, offline contemporary modalities such as television, and the digital world of the Web, bringing them together into a single unified collection.

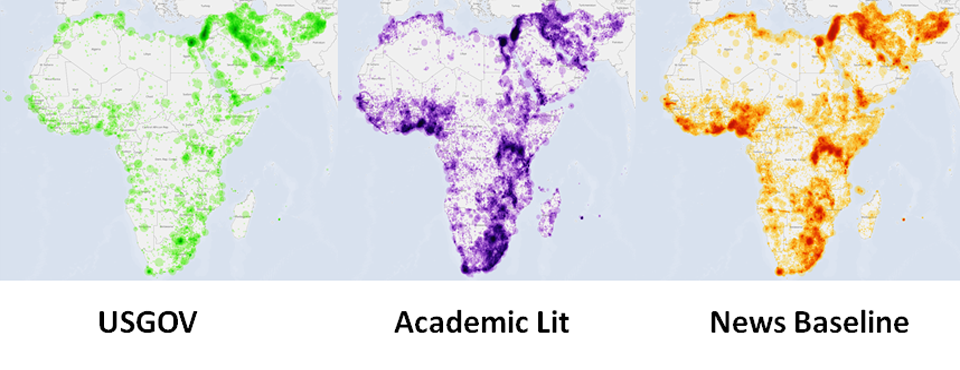

Starting with the Knight-funded Television News Archive, last fall I geocoded all half million hours of closed captioning, creating a series of maps that made it possible to access television not as time codes or keyword searches, but as sequences of map points reflecting the geography of American television news coverage. All the geographic biases of the media become instantly clear, and a journalist can instantly immerse herself in all available coverage of an emerging event. A month ago I released a tool that extends this to time, allowing one to type in a set of keywords or phrases and instantly see their usage over the last half decade, which networks emphasize those terms, and to export a list of the words that appear most frequently alongside those terms. A journalist could rapidly see how portrayal of Congress is changing or that certain political issues are being discussed together more frequently.

This past spring I wondered about the ability to reshape how we interact with our history. As libraries digitize their print holdings, does the digital form offer the ability to rethink what a “book” is? In particular, what if we thought of books not merely as collections of words, but as galleries of the world’s greatest collection of visual history? Ultimately I processed all 600 million pages of the archive’s digitized book collection dating back more than 500 years and extracted every image from each page, along with its surrounding text and metadata. The searchable collection of 14.7 million images is now available on Flickr, creating a visual archive of half a millennia of world history.

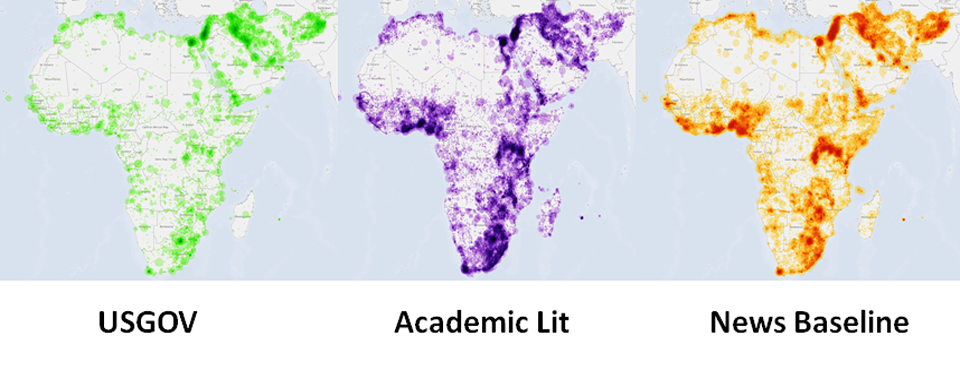

This past summer, I worked with the archive to conduct the very first pilot content mining of its Web archive, scanning its more than 1.7 billion PDFs for academic literature on Africa and the Middle East posted on the Web since 1996. In the place of keyword searches, policymakers and journalists can now instantly access the combined socio-cultural knowledge of the social sciences and humanities in the regions, mapping food insecurity or ethnic strife, and identifying top experts on a particular locality.

Each of these projects explores what is possible when libraries open their collections to data scientists, allowing them to apply data mining algorithms to catalog, mine, visualize and create new ways of interacting with these vast archives. The results of such “big data” analyses by this new generation of “data librarians” yields new tools and datasets that can subsequently be used by ordinary citizens and journalists to transform how they access and understand the world.

Perhaps the future of libraries lies in a return to their roots, not as museums of physical artifacts for rental, but as conveners of information and those who can understand and translate that information to the needs of an innovative world.

To submit an entry for the Knight News Challenge or provide feedback on other submissions, visit newschallenge.org. Knight News Challenge: Libraries closes today, Tuesday, Sept. 30, 2014, at 5 p.m. ET. Winners will be announced in January.

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·